Introduction and Context

Computer Vision (CV) is a field of artificial intelligence that focuses on enabling machines to interpret and understand visual information from the world, similar to how humans do. One of the most significant advancements in CV has been the development of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which have revolutionized the way we process and analyze images and videos. CNNs are a class of deep learning models specifically designed to handle the hierarchical structure of visual data, making them highly effective for tasks such as image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation.

The importance of CNNs in CV cannot be overstated. They have enabled breakthroughs in various applications, from self-driving cars to medical imaging and security systems. The first CNN, LeNet, was developed by Yann LeCun in 1989, but it wasn't until the advent of large-scale datasets like ImageNet and the availability of powerful GPUs that CNNs truly took off. The AlexNet model, introduced in 2012, marked a turning point, achieving unprecedented accuracy on the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC). Since then, CNNs have become a cornerstone of modern CV, addressing the technical challenge of extracting meaningful features from raw pixel data and making sense of complex visual scenes.

Core Concepts and Fundamentals

The fundamental principle behind CNNs is the ability to learn hierarchical feature representations from input images. This is achieved through a series of convolutional layers, each of which applies a set of learnable filters (or kernels) to the input data. These filters detect specific patterns or features, such as edges, textures, and shapes, at different levels of abstraction. The output of each convolutional layer is passed through a non-linear activation function, typically ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit), to introduce non-linearity into the model.

Key mathematical concepts in CNNs include the convolution operation, which is a dot product between the filter and the local regions of the input. This operation is performed across the entire input, resulting in a feature map that highlights the presence of the detected feature. Another important concept is pooling, which reduces the spatial dimensions of the feature maps, helping to make the model more computationally efficient and less prone to overfitting. Common types of pooling include max pooling and average pooling.

CNNs differ from other neural network architectures, such as fully connected networks, in their ability to exploit the spatial hierarchy of visual data. While fully connected networks treat the input as a flat vector, CNNs maintain the 2D structure of the input, allowing them to capture spatial relationships between pixels. This makes CNNs more efficient and effective for processing images and videos.

Analogously, think of a CNN as a detective who starts with broad clues (low-level features like edges) and gradually narrows down to specific details (high-level features like objects). This hierarchical approach allows the model to build a comprehensive understanding of the visual scene, much like how a human would process an image.

Technical Architecture and Mechanics

The architecture of a typical CNN consists of several key components: convolutional layers, pooling layers, fully connected layers, and normalization layers. The process begins with the input image, which is fed into the first convolutional layer. Each convolutional layer applies a set of filters to the input, producing a set of feature maps. For instance, in a simple CNN, the first layer might detect edges, while subsequent layers might detect more complex shapes and objects.

The convolution operation can be described as follows: for each position in the input, the filter slides over the input, computing the dot product between the filter and the local region of the input. This results in a single value in the feature map. The filter is then moved to the next position, and the process is repeated until the entire input has been covered. The size of the filter, the stride (the step size for moving the filter), and the padding (adding zeros around the input to control the output size) are key design decisions that affect the model's performance.

After the convolutional layers, pooling layers are often used to reduce the spatial dimensions of the feature maps. Max pooling, for example, takes the maximum value within a local region, effectively downsampling the feature map. This not only reduces the computational load but also helps to make the model more robust to small translations and distortions in the input.

The feature maps from the convolutional and pooling layers are then flattened and passed through one or more fully connected layers, which perform the final classification or regression task. Normalization layers, such as Batch Normalization, are often used to stabilize and accelerate the training process by normalizing the inputs to each layer.

Modern CNN architectures, such as ResNet, Inception, and EfficientNet, have introduced several innovations to improve performance and efficiency. For example, ResNet uses residual connections, which allow the model to learn identity mappings, making it easier to train very deep networks. Inception networks use a combination of convolutional filters of different sizes in parallel, allowing the model to capture multi-scale features efficiently. EfficientNet, on the other hand, uses a compound scaling method to scale up the depth, width, and resolution of the network, achieving state-of-the-art performance with fewer parameters.

Advanced Techniques and Variations

Recent advancements in CNNs have focused on improving their performance, efficiency, and generalization. Attention mechanisms, for example, have been integrated into CNNs to allow the model to focus on the most relevant parts of the input. Self-attention, as used in the Transformer model, calculates the relevance of each part of the input to every other part, allowing the model to weigh the importance of different features dynamically. This has been particularly effective in tasks such as image captioning and visual question answering.

Another significant development is the use of dilated convolutions, which increase the receptive field of the filters without increasing the number of parameters. This allows the model to capture larger contextual information, which is beneficial for tasks such as semantic segmentation. Additionally, deformable convolutions, introduced in the Deformable Convolutional Networks (DCN) paper, allow the filters to adapt their shape and position based on the input, providing more flexibility and better handling of geometric variations.

State-of-the-art implementations, such as the Swin Transformer, combine the strengths of CNNs and Transformers. The Swin Transformer uses a hierarchical structure with shifted windows, allowing it to capture both local and global context effectively. This has led to significant improvements in tasks such as image classification and object detection.

Different approaches, such as NAS (Neural Architecture Search), have also been explored to automatically find optimal CNN architectures. NAS methods, such as DARTS (Differentiable Architecture Search), use gradient-based optimization to search for the best architecture, leading to highly efficient and effective models. However, these methods often require significant computational resources and time.

Practical Applications and Use Cases

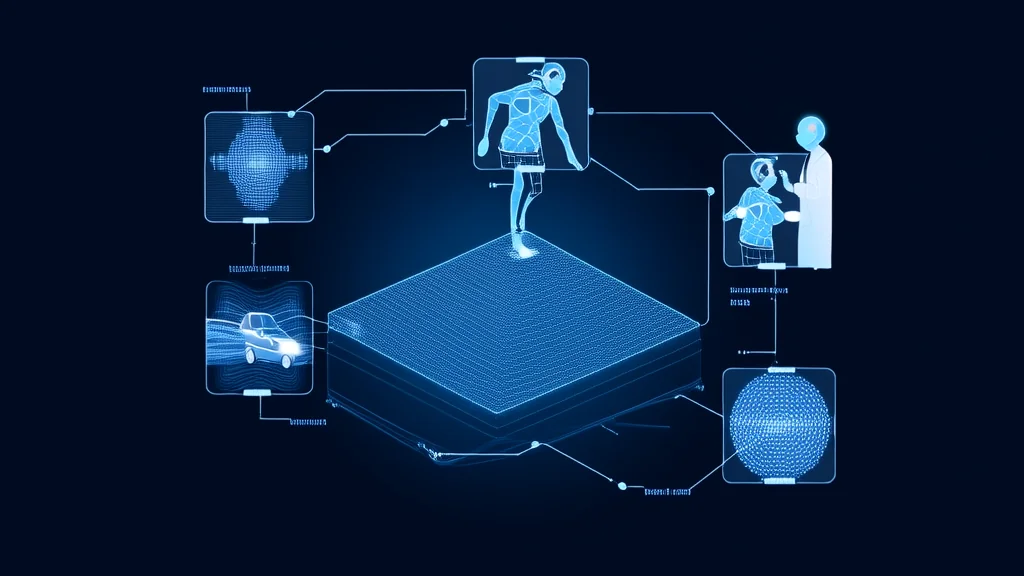

CNNs and their advanced variants are widely used in a variety of real-world applications. In the field of autonomous vehicles, CNNs are used for object detection and recognition, enabling the vehicle to identify and track other vehicles, pedestrians, and obstacles. For example, Tesla's Autopilot system relies heavily on CNNs for its perception tasks. In medical imaging, CNNs are used for tasks such as tumor detection, lesion segmentation, and disease diagnosis. Google's DeepMind has developed CNN-based models for diagnosing eye diseases from retinal scans, achieving performance comparable to that of human experts.

In the consumer electronics industry, CNNs are used for facial recognition and biometric authentication. Apple's Face ID, for instance, uses a combination of infrared cameras and CNNs to securely authenticate users. In the field of security, CNNs are used for surveillance and monitoring, enabling real-time detection and tracking of suspicious activities. For example, the NVIDIA Metropolis platform uses CNNs to analyze video streams from security cameras, providing real-time insights and alerts.

What makes CNNs suitable for these applications is their ability to learn and extract meaningful features from raw pixel data, combined with their robustness to variations in the input. In practice, CNNs have shown excellent performance in terms of accuracy, speed, and scalability, making them a go-to choice for many CV tasks.

Technical Challenges and Limitations

Despite their success, CNNs face several technical challenges and limitations. One of the main challenges is the need for large amounts of labeled training data. CNNs, especially deep ones, require extensive and diverse datasets to generalize well to new, unseen data. This can be a significant barrier in domains where labeled data is scarce or expensive to obtain. Transfer learning, where a pre-trained model is fine-tuned on a smaller dataset, has been a popular solution to this problem, but it still requires some amount of labeled data.

Another challenge is the computational requirements of CNNs. Training deep CNNs can be computationally intensive, requiring powerful GPUs and significant memory. This limits their accessibility to researchers and developers with limited resources. Efforts to address this issue include the development of more efficient architectures, such as MobileNet and ShuffleNet, which are designed to run on resource-constrained devices.

Scalability is also a concern, especially for real-time applications. While CNNs can achieve high accuracy, they may not always meet the latency requirements for real-time processing. Techniques such as model pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation have been proposed to reduce the computational and memory footprint of CNNs, making them more suitable for real-time applications.

Research directions addressing these challenges include the development of more efficient and scalable architectures, the use of unsupervised and semi-supervised learning to reduce the need for labeled data, and the exploration of novel hardware accelerators to improve the computational efficiency of CNNs.

Future Developments and Research Directions

Emerging trends in the field of CNNs and computer vision include the integration of multimodal data, the use of self-supervised learning, and the development of more interpretable and explainable models. Multimodal learning, which combines visual, textual, and other types of data, has the potential to enhance the performance and robustness of CV models. For example, combining images and text can provide richer context and improve tasks such as image captioning and visual question answering.

Self-supervised learning, where the model learns from unlabeled data, is another active area of research. Techniques such as contrastive learning and masked autoencoders have shown promising results in learning rich and transferable visual representations without the need for labeled data. This has the potential to significantly reduce the reliance on large labeled datasets and make CV more accessible and scalable.

Interpretable and explainable models are also gaining attention, as there is a growing need to understand and trust the decisions made by AI systems. Techniques such as attention visualization, saliency maps, and layer-wise relevance propagation (LRP) are being developed to provide insights into the internal workings of CNNs and highlight the features and regions of the input that contribute to the model's predictions.

From an industry perspective, the focus is on developing more efficient and scalable solutions that can be deployed in real-world applications. This includes the development of edge AI, where models are run directly on edge devices, and the integration of CV into broader AI ecosystems. From an academic perspective, the focus is on pushing the boundaries of what is possible with CV, exploring new architectures, and addressing the fundamental challenges of learning, generalization, and interpretability.

Overall, the future of CNNs and computer vision looks promising, with ongoing research and development likely to lead to even more powerful and versatile models that can tackle a wide range of real-world problems.